There are lots of helpful principles to use when writing or delivering a talk or speech. This post addresses the more narrow matter of organizing a talk. If your talk is well organized, people will understand your ideas better, you’ll be able to remember your content better and not get lost or distracted as easily, you’ll be able to adjust your talk on the fly, and as a result, you’ll probably be more relaxed while giving it. (Note, this post does not apply as much to giving lessons, which are a very different animal.)

I have found two concepts in particular to be very helpful in giving structure to a talk. The first idea is found in scripture and philosophical writings, but my attention was first drawn to it by … er, well, I’ll just be honest. I got it from the video game series The Legend of Zelda, specifically from the item called the triforce (now that I’ve outed myself as a special cross-breed of geek, I might elaborate more on that source of insight in a future post). The second idea came from my Mom. She’d heard it from somewhere else and shared it with me when I was in high school. Combining these two concepts can go a long way toward bringing order to the chaos of the important ideas you want to get across. It doesn’t apply to every kind of talk, but I’ve used it in some form for virtually any occasion (most often when speaking in church).

1. Sort your main ideas using three types of questions

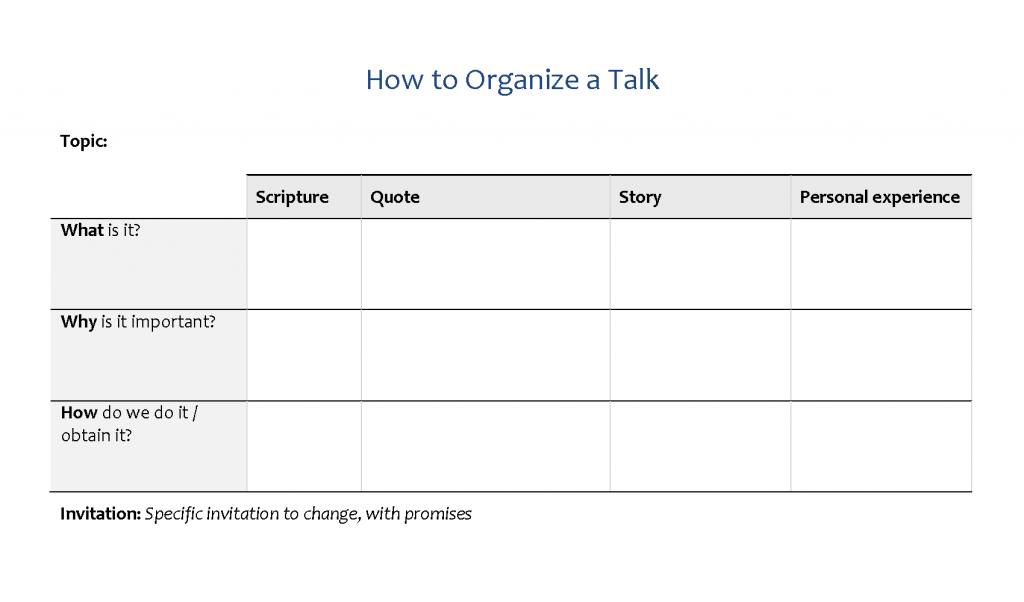

First, categorize your ideas according to the answers they give to the following three questions:

- What is it?

Define your topic. Give examples of it. Contrast it with its opposite, or with its counterfeit. - Why does it matter?

Why should the audience care about this topic? Why is it important or relevant, to them personally or to people generally? What would they get out of understanding it or acting on it? - How does one do it?

What specific steps can the audience take in the immediate future to act on this information? What instructions do they need? What does it look like when a person gets this right? When one doesn’t get this right? What obstacles should they watch out for, and how can one get around them?

Other labels could be used for these three categories. Instead of labeling them What, Why, and How, you could label them Informative, Motivational, and Instructional. Or, Knowledge, Desire, and Ability. Or, Mental, Spiritual, and Physical. (Or from my original source of inspiration, Wisdom, Courage, and Power.) These three things make up the left column in the chart below.

The sequence isn’t set in stone, but it’s usually best to do it in this order. Here’s why. The gospel is a message of choices and actions, so a talk is kind of useless if it doesn’t lead to someone changing, acting, doing something about it (#3 How). But a person isn’t going to do something until they see the reasons they ought to do it (#2 Why). And a person can’t understand why they should do something until they first understand what that something is, at least at a basic, introductory level (#1 What). Hence the order of the questions.

For example, let’s say you’re speaking on tithing. If you get straight into the minutiae of decimals and division, or the clever ideas like triple-slotted piggy banks (#3 How), your audience might tune out unless you’ve first motivated them to care about those concrete suggestions by describing the blessings of tithing (#2 Why). And you might have several persuasive and penetrating quotes about how important it is to live the law of tithing (#2 Why), but an audience member will be totally lost for the duration of your talk if you never define what you mean by the word “tithing” (#1 What).

If you were to use the three questions to organize the main ideas of your talk, your outline might look something like this:

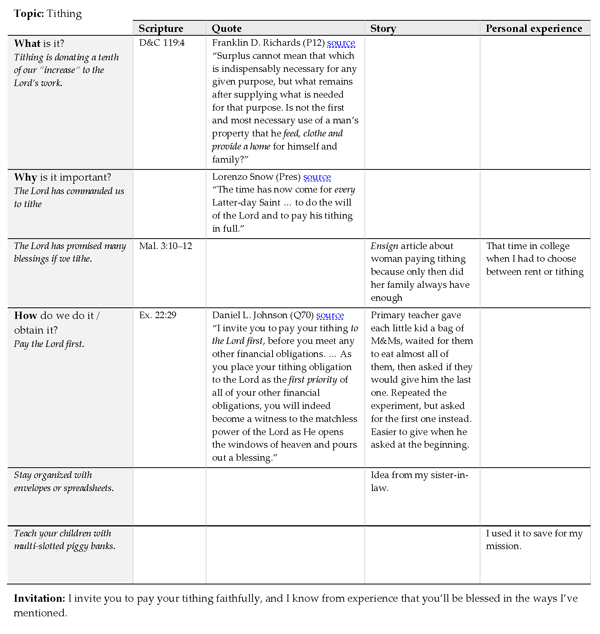

Topic: Tithing

Invitation: I invite you to pay your tithing faithfully, and I know from experience that you’ll be blessed in the ways I’ve mentioned. |

2. Sort your sources under each main idea

Once you have the main ideas you want to get across, in the order you want to mention them, start gathering sources that teach those ideas. Most sources fall into one of the following types:

- Scripture passages

- Quotations (especially from modern prophets)

- Stories from others (especially from modern prophets)

- Personal experiences

Each source is important for different reasons. Scriptures and quotations from prophets have the weight of authority, so people know these aren’t just your own ideas you made up. Stories are by far the most impactful thing to share (if you remember nothing else from a talk, you remember the stories). And stories from your own life (personal experiences) are what make the talk your unique contribution; they’re a way of sharing your own individual witness of an already established doctrine. These labels make up the top row in the chart above.

For each type of source, ask yourself, which main idea does this source support or teach? Does it define the topic? (#1 What.) Does it tell why we should believe or do something? (#2 Why.) Does it explain the process or steps for acting on this idea or living it in your own life? (#3 How.) List them on your outline under the pertinent main idea. If you were preparing a talk on tithing, your outline might now look like this:

Topic: Tithing

Invitation: I invite you to pay your tithing faithfully, and I know from experience that you’ll be blessed in the ways I’ve mentioned. |

Note that you do not need to have one of each type of source under each question. For example, when you’re giving a definition (#1 What), you don’t often use stories; you’re more likely to use a scripture or a quotation. Also note that on a real outline, you might have each quote in its complete form pasted right into the outline, or you might choose to have the complete quotes on a separate piece of paper—whichever works for you.

Advantages

There are several advantages of planning your talk like this. For one thing, it keeps you from forgetting your purpose. Have you ever finished telling a story or reading a scripture, only to realize that you can’t remember why you shared it? This outline helps remind you of the purpose of each source that you use. Just glance above the source at the main idea that it is intended to support. Then conclude your reading of the quote with a recapitulation of that main idea.

Also, this kind of outline is very useful when you need to shorten your talk at the last moment. If the speaker before you uses all the time, so that you now have only 7 minutes to give your 20 minute talk, just cut out some of the less important ideas or some of the redundant sources. That way you can still get across the most important ideas of your talk, even if you only have a fraction of the time.

Click here to see custom editions of the scriptures that you can download for free.

For example, lets say the long-winded speaker before you spends half an hour explaining how her carbuncles were healed. You need to shorten your talk. You’re not nervous or flustered, though, because you’ve prepared beforehand by deciding which main ideas are crucial and which ones could be sacrificed without making the talk unintelligible, scattered, or liable to be misinterpreted. You’ve also decided that, while each of your sources is insightful and beneficial, if you had to limit yourself to just a few, you know which ones are your favorites. When you’ve prioritized your main ideas and sources like this, simply drop out the non-crucial ones and your talk is easy to give in less time, without dramatically altering its logic or organization.

I sometimes prioritize my talks using light grey text. I write out the whole thing (or outline it). Then I go through asking myself which ideas or sources could be omitted if absolutely necessary. I select these and color them grey—dark enough to read, but noticeably light so that I can tell at a glance which ideas to skip (I’ve even used three or four levels of color before, to prioritize among vital, important, fine, and “extra”). Then I print it out like that. Using the tithing example, the outline would now look like this:

Topic: Tithing

Invitation: I invite you to pay your tithing faithfully, and I know from experience that you’ll be blessed in the ways I’ve mentioned. |

Some advice about prioritizing. I emphasize authoritative quotes or scriptures for anything that could be remotely controversial, because it removes me as the source of the idea and leaves the concerned person to grapple with the quote rather than with me. In the example above, let’s suppose someone decided she didn’t like the idea of “Pay the Lord first” and thought I was being insensitive and elevating something that was merely my personal opinion (I don’t anticipate an objection like this, but hey, you never know). If I had simply stated the idea and only elaborated on it by telling the story about the Primary children, the concerned ward member would be confident, in her mind, that it was just my opinion, inappropriately given air time at the podium. But if I also include the quote from a member of the Seventy, published in a Church magazine, that should help allay her fears.

When it’s not a matter of establishing an idea’s legitimacy, I give highest priority to stories, especially personal experiences, for two reasons. First, stories are more effective than explanations, generally speaking. Concrete narratives dive deeper into our hearts than abstract expositions (there are exceptions, of course). It’s one reason the Lord used parables. It’s one reason people know the books of Exodus and Luke better than they know Proverbs and Ephesians (it’s also why the Doctrine and Covenants can be so hard to get acquainted with). And when it’s a story that happened to you, the telling is even more powerful. You can elaborate on details that seem to interest your particular audience. and there’s no doubting the unique impact of hearing a first-hand account of even the most mundane spiritual experience.

Second, you have been asked to give a talk and to share your testimony related to the principle or doctrine at hand. If that weren’t so, then we would all just stand up and read general conference talks. After all, their authors are far more knowledgeable and authoritative. But we’re not supposed to do that; we’re supposed to bear testimony. We do that by telling the experiences we have had personally in trying to live a gospel principle or commandment. There’s a power in sharing how the Lord’s promises have been fulfilled in your life. As Orson Scott Card put it,

I’m not a prophet, … nor am I a scholar. … What I know are things that many people know; what I say are things that other people have said. And yet I know from experience that you can hear a thing a hundred times, and not only never understand it, but never even understand that you haven’t yet understood it. Then, suddenly, you hear the same thing, but spoken in a different way, or in a different context, or simply by a different person—and lo! The idea that has eluded you for so long suddenly opens up to you, because at last you are ready to receive it, or at last someone has said it in a way that allows you to understand.

There’s a chance that when I speak what truth I’ve learned in my limited experience, there will be [listeners] who have been waiting to hear it in the way I’ve learned to say it. There will be [listeners] who happen to be open, at this moment, to being touched by the Spirit of understanding.1

Conclusion

For those who think in pictures, here’s the same talk, but displayed as a chart instead of an outline. This might be useful for, say, quickly assessing whether you’ve done a good job of using a variety of sources, peppering your talk with both scriptures and stories, etc.

Click on the Microsoft Word icon near the beginning of the article to download a Word document with a blank outline view, as well as a blank chart view, ready to be filled in.

I hope this combination of ideas help you more easily prepare and give talks. I found it especially helpful when I was first learning how to do public speaking. Once you get more experience, you can safely stray from this format to do things in a little more novel or creative way, but I think this is a good foundation to start with. I’d love to hear your feedback if you found this useful, or if you have any further ideas.

1. Orson Scott Card, A Storyteller in Zion (Salt Lake: Bookcraft, 1993), p. 4.

This was excellently written and organized. What a great resource. Thanks!

This is good, really good. Now I pray I never have to use it! Ha! Thanks!

This is extremely helpful and well written out, thank you so much!

Dear Nathan,

Your publishing this outline of how to organise a talk is a great service to the world. I am grateful. Thank you.

The graphical representation of a talk really helps me see how to quickly organize my thoughts so that they will be coherent to others. Thank you.

I would really be interested in how to organize a lesson. I took your table and reproduced it 4 times, thinking that a lesson is really just 4 talks put together. I am not sure that is accurate.

Do you have a method for organizing lessons? I teach Gospel Doctrine.

Great question, Tamlyn. I think a lesson is very different from a talk in several significant ways.

For one thing, with a talk, you don’t really have to plan much in the way of audience interaction. In contrast, with a lesson, you’re specifically trying to find ways to help the learners arrive at insights on their own as much as possible, rather than just lecturing to them. Generally speaking, a good lesson has the learners speaking more than the teacher. This is often done, for example, by asking a thought question, having the learners search a short passage for the answer, then talking about how that passage answers the question. Then asking how that applies to our lives, and whether anyone has any examples or experiences of applying it. In a talk, this is all done by the speaker; in a lesson, the speaker might only end up asking questions, whereas all the insights are supplied by the class members.

For another thing, the structure of the lesson depends a lot on the content matter. The Gospel Principles manual is topical, so it would actually work pretty well to use this talk outline to organize a Gospel Principles lesson.

However, Gospel Doctrine is currently scripture-sequence-based, meaning each lesson is not centered on a topic, but rather on a passage of scripture. So the outline is frequently not What-Why-How regarding a topic, but rather a stream of often-unrelated principles that can be drawn out of the scripture narrative. So in that case, I wouldn’t use this talk outline at all. Instead, I use a few different ways of structuring my lessons, depending on how I feel like the passage needs to be approached.

That’s my quick and dirty reply. I hope that helps. You’ve rekindled my interest in writing a follow-up post to this one, on how to organize a lesson. Eventually!