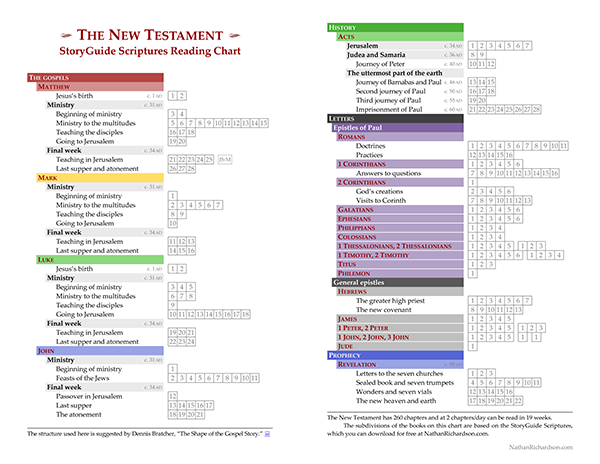

Several nifty reading charts are out there for keeping track of your progress as you read the standard works (for example, they hand one out with the seminary Scripture Mastery cards; other charts form a picture). This one, however, is different because it also depicts the larger structure of the New Testament, to help you get the big picture. Most books (the larger ones) have major and minor subdivisions. For example, Acts subdivides into three main parts, based on the Savior’s statement at Acts 1:8 that “Ye shall be witnesses unto me both in Jerusalem [ch. 1–7], and in all Judæa and in Samaria [ch. 8–12], and unto the uttermost part of the earth [ch. 13–28].”

StoryGuide Scriptures Reading Chart: New Testament

The subdivisions I chose are based in part on the StoryGuide Scriptures—a customized version of the standard works I have created, which lays out the (unchanged) authorized text in paragraphs and with headings, so it looks more like a modern novel or textbook. If you’re interested in reading an edition of the scriptures that uses headings to depict this chart’s subdivisions in the actual text as you read, follow the link above. You can download it for free. [Note: The New Testament is not completed yet.]

Explanations

The Books of the New Testament can fit into four basic groups or genres:

- The Gospels (dark red) (Matthew–John), which tell the story of Jesus’s mortal life and ministry, from his birth to his death and resurrection.

- History (dark green) (Acts), which tell the story of the Apostles’ ministry after Christ’s resurrection and ascension to heaven.

- Letters (dark grey) (Romans–Jude), which were written by a variety of Church leaders to a variety of audiences, at different times in the first century after Christ’s ministry. Another word for letters is epistles.

- Prophecy (dark blue) (Revelation), which tells of future events before Christ comes again.

Within these top-level groups, I have shaded the names of the some books based on the author.

- Matthew (red) wrote the gospel of Matthew.

- Mark (yellow) wrote the gospel of Mark. There’s a fairly reliable tradition that he was also Peter’s assistant and scribe, so Peter (the author of the letters of 1 and 2 Peter) may have had a strong influence on the content of the gospel of Mark.

- Luke (green) wrote the gospel of Luke, as well as Acts (compare Luke 1:1–4 with Acts 1:1–2). The themes and structure are so closely related that scholars sometimes refer to them as a single book called Luke-Acts.

- John the apostle (blue) wrote the gospel of John, as well the three letters of 1, 2, and 3 John, and the book of Revelation.

- Paul (purple) wrote the first subgroup of letters, Romans–Philemon.

Note that this is the same coloring system I used in my Come Follow Me Reading Schedule for the New Testament.

I have not color shaded the second subgroup of letters because they have a variety of different authors. This second subgroup is called the General Epistles because they are written to a general audience of all Church members rather than to specific individuals or congregations.

You can see from this that most of the New Testament was written by these five authors. The remaining books were written by at most four other authors. The books of James and Jude were written by Jesus’s two brothers (mentioned at Matt. 13:55 / Mark 6:3). The books of 1 Peter and 2 Peter were written by Peter, and for that reason I have colored them yellow to match the gospel of Mark on the Come Follow Me Reading Schedule for the New Testament. With the book of Hebrews, we don’t know who the author is; the extant book doesn’t say. People have proposed various authors, including Paul, Luke, Barnabas, Apollos, or Timothy, but we really don’t know.

Within the individual books, the longer ones are further divided into major and minor subdivisions (corresponding to “parts” and “units” in the StoryGuide edition of the scriptures. For the book subdivisions within the gospels, I used the structure suggested by Dennis Bratcher; among other things, it can make it easier to compare passages between two gospels. For the book subdivisions within other books, I looked for ones that seemed natural to the text. In the case of Revelation, I learned in Jeffrey R. Chadwick’s New Testament class how Revelation 4–11 parallels 12–16 in several important ways, akin to other passages where the same meaning is conveyed twice, through two different sets of symbols or visions (Joseph’s dreams at Gen. 37:7–10, Pharoah’s dream at Gen. 41:1–7, and Daniel’s visions at Daniel 2 and 7).

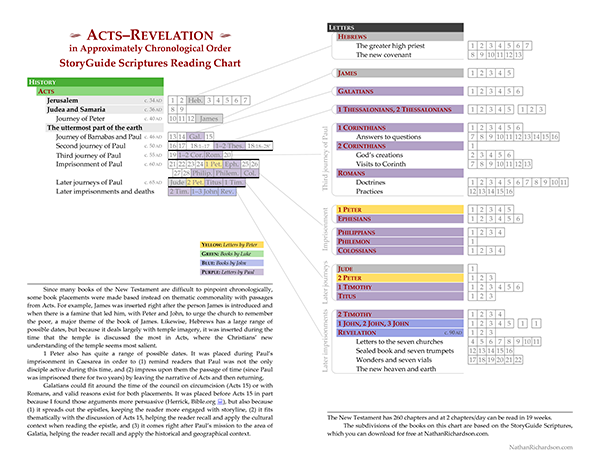

Chronological Reading Chart

The second page of this PDF document rearranges the latter books of the New Testament (omitting the gospels) to help you read the New Testament in roughly chronological order.

The first time I read the New Testament was my freshman year of seminary. I remember finding the stories (Matthew–Acts) very interesting and easy to follow. But then when we got to the letters, while there were a few topical passages that made sense on their own, by and large they were a bewildering assortment of ideas, quotations, and mentions of people, places, and events, some of which sounded sort of familiar. My teacher and manual would point out that, e.g., Romans was written after the events of Acts were finished. Then we got to 1 Corinthians and I realized it was written years before Romans, back during one of Paul’s missions.

I thought, “Why are we reading these out of the order they happened in? And why didn’t we read these during the part of the story when they happened?” I intuitively knew it would have made more sense to me, as a first-time reader, to pause our reading of Acts and jump over to read a letter that was written at that point in the story, then return to Acts and pick up the narrative again. That’s why I created this chronological reading checklist. It’s the way I wish I could have read the New Testament the first time.

Much of New Testament chronology is uncertain of course, but we can make some educated guesses. My primary concern was helping the user read each of the letters in the most relevant historical context available, most of which is provided by the book of Acts.

So for example, while we don’t know very well when Hebrews or James were written, I thought it most helpful to read them during the parts of Acts that are most related to each book—that discuss some of the same themes or people. Hebrews is focused on the temple, and how Jesus Christ is foreshadowed by many of the temple ceremonies in the law of Moses. So it seemed best to read Hebrews at whatever point in Acts discusses the temple the most. That would be at the beginning, when all the apostles were in Jerusalem (Acts 1–7), or near the end, when Paul is arrested at the temple (Acts 21–23). I had already noticed that most of the epistles are clustered in the latter half of Acts, so I favored inserting Hebrews near the beginning. Hebrews also helps make sense of several details in the narrative of Acts, such as why Christ’s disciples loved meeting at the temple so much (Acts 2:46–3:3; 5:12, 20–21, 25, 42), or why so many Levites and priests recognized Jesus as the Messiah (Acts 4:36; 6:7).

Likewise, I inserted the book of James right after the person James is introduced (Acts 12:17). This event happens during a famine, which led to Church leaders sending relief to the poor and hungry (Acts 11:28–29). As it turns out, charitable aid to the poor is one of the major themes in the book of James (James 1:9–10, 27; 2:1–9, 15–17, 5:1–6). So it made perfect sense to insert James at the end of chapter 12. It also serves as a break between part 2 (Judea and Samaria) and part 3 (All the Earth).

If you’re interested in any of my other book placements, ask in the comments below and I’ll add my reasoning to this page.

I really can’t recommend highly enough to read the New Testament in a chronology like this. It makes the letters of Paul make wayyy more sense. Each time the Church has read New Testament for the Come Follow Me program, I have strayed from the standard reading schedule in order to teach my kids in the chronological order. (They end up a little out of synch with their Sunday school lessons, but it’s minor and is more than compensated by increased understanding.)

I have found that all of them, even the younger ones, gain a far better grasp of the storyline, thus making the letters of Paul more meaningful. When Paul mentions Apollos in 1 Corinthians (which we read in the middle of Acts 19), it’s no sweat—they know who Apollos is because they were just introduced to him a few days earlier when we read Acts 18. When we read Galatians, they know where Galatia is because we just read about Paul’s mission there (Acts 13–14). When we read Paul defend himself at Eph. 2:11–22 regarding his views on the temple, the law of Moses, and Gentiles, it makes perfect sense because we just read those three accusations made by the Jews who mobbed him at Acts 21:28 (thank you, Dr. Fred Long).

Closing

I hoped this explanation has helped you know how to best use this chart for yourself and your family. If you have any questions or suggestions for improvement, I’m all ears; please comment below.

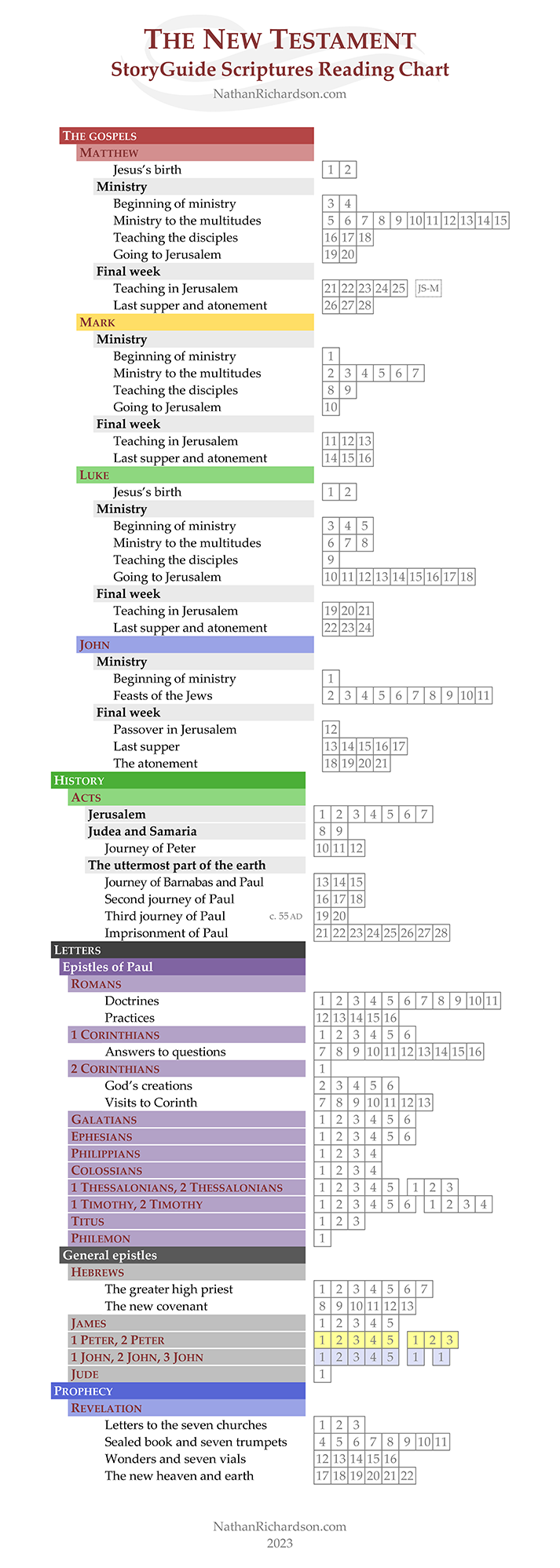

And just to satisfy that bird’s-eye itch, here’s a Pinterest-friendly version of the whole chart in one continuous column: