One of these dynasties is not like the other! Now that you’ve noticed the difference, what does that tell us about God?

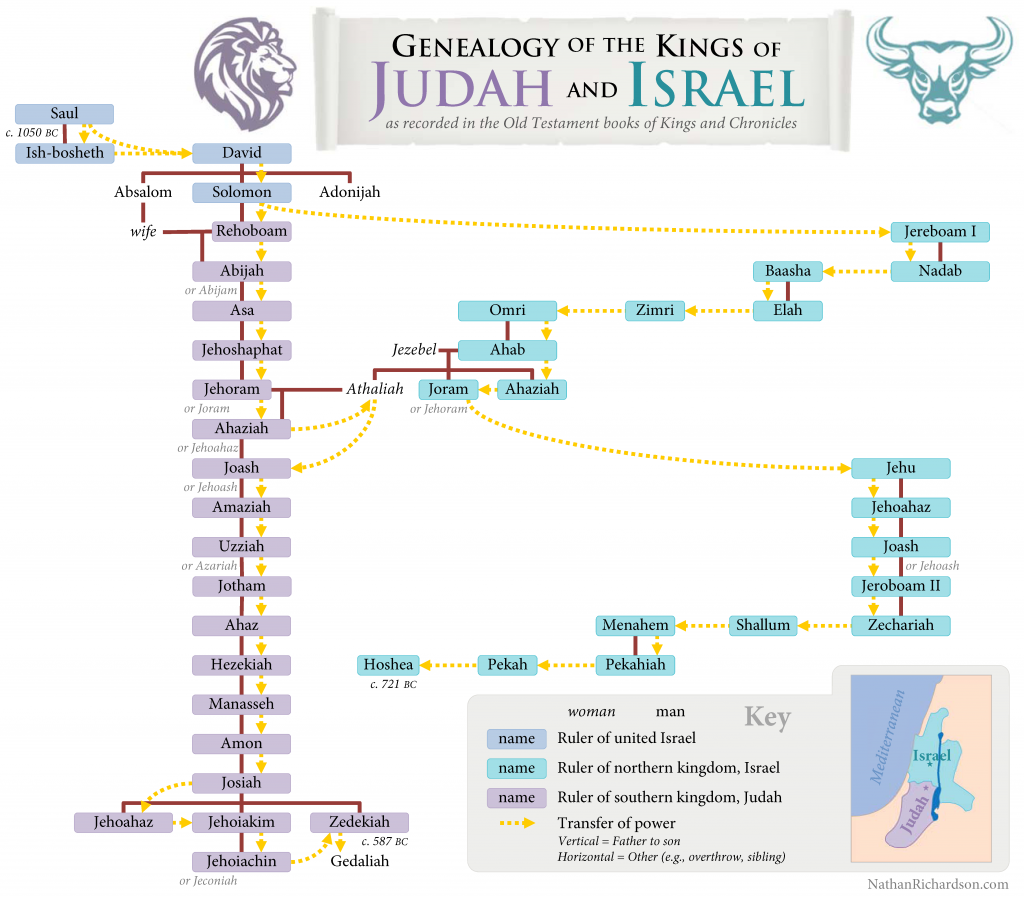

The Old Testament books of Kings and Chronicles are important because they provide the storyline in which half of the other Old Testament books occur. For example, if you want to know what the heck Isaiah is talking about in Isaiah 7–8, you need to know the storyline provided in 2 Kings 16. One difficulty in reading Kings and Chronicles, however, is that in many cases, two different people share the same name. For example, there are two kings named Jeroboam. And sometimes, one person has two different names. For example, there are two kings named Joram, each of whom is also called Jehoram in some passages (likewise, there are two kings named Joash, each of whom is sometimes called Jehoash). Even more confusing, there are two kings named Ahaziah, but one of them is sometimes called Jehoahaz; that “nickname” might help to distinguish them, except that there is yet another king who is already named Jehoahaz.

What a mess! When you’re reading a passage, how do you keep straight who it’s talking about? This is why charts and diagrams can be so helpful. In my latest bout of reading in Kings and Chronicles, I searched online for a concise chart of the kings of Israel. There were several decent options on the web, with unique layouts depicting the same information in different ways. Here are some of the ones I found, in order of least- to most-liked by me:

- Dave Lamb, “Family Tree of the Kings of Israel and Judah,” DavidTLamb.com.

- “Genealogy of the Kings of Israel and Judah,” Wikimedia Commons

- “The Genealogy of the Kings of Ancient Israel and Judah,” from BritAm.org.

Dave Lamb’s (#1) uses distinct colors for the two kingdoms. Wikimedia’s (#2) improves on that by using horizontal shifts whenever there was a coup resulting in a new dynasty (the changes in dynasty are an important part of the overarching story in Kings, which is why I reflected that in the outline of Kings on my Structural chapter reading chart of the Old Testament). And chart #3 improves on that by adding yellow lines to show a transfer of power, which is especially useful at the end, when three of Josiah’s sons become king at different times.

I decided to make a few more improvements, such as making the power-transfer lines curved, so that it’s easier to distinguish them from the right-angled genealogy lines (contrast that with graphic #3 above to see how it helps). For the colored boxes around the kings’ names, I chose colors to match my scripture timeline (forthcoming post), with blue representing the united people of Israel (think blue sky—heaven—God’s chosen people); and for the divided kingdoms, I used the two colors on either side of blue on the color wheel: the lighter turquoise-blue for the northern kingdom (think “Israel Lite, now with 16% fewer tribes!”), and purple for the southern kingdom (think royal purple, since they were ruled by the royal house of David). I also added a map that uses the same color coding, to jog your memory about which kingdom was north and which was south (I had to relearn that a dozen times before it stuck). My wife found a neat scroll image, which I used because you have to have a scroll for Bible-related graphics!

Finally, I added a lion (source) and an ox (couldn’t refind the source; sorry, artist), the two tribal emblems for the tribes of Judah and Ephraim (Ephraim was the principle tribe that represented the entire northern kingdom in many passages; e.g., Isa. 7:17; 11:13; Ezek. 37:16, 19; Hosea 5:5, 12–14). This Israelite heraldry has a long tradition, based in part on the tribal blessings recorded in Genesis 49 and Deuteronomy 33 (for Judah as a lion, see Gen. 49:9 and Rev. 5:5; for Ephraim as an ox, see Deut. 33:17, although the King James Version mistranslates it as unicorn). I literally searched for hours until I found just the right images (those of us who have no computer illustration know-how are at the mercy of Google image searches), because a good graphic can turn a dry diagram into a classier, memorable visual.

So what? What lessons can I learn from this chart?

We’re used to examining individual verses and phrases in our scripture study, but many scriptural lessons are found in overarching patterns that span several chapters or books. Some of those patterns and lessons are easier to see with charts like this.

One of the first patterns to notice is the difference in dynasties between the two kingdoms. The northern kingdom, Israel, had a continuous cycle of regicide and usurpation; only two of its dynasties survived more than two generations. In contrast, the southern kingdom, Judah, had a single unbroken dynasty (descending from David), an enviable source of stability that would be desired by any monarchy in history. While the kings of Judah were not perfect, their relative righteousness compared to Israel is a reminder that obedience brings blessings. This enduring royal line of the southern kingdom also evokes promises regarding David and the house of Judah (e.g., Gen. 49:10; 2 Sam. 7:12–16; 1 Kgs. 9:5; Ps. 89:35–36; Jer. 33:17).

Another notable segment of the two royal lines is where they connect—when King Jehoram of Judah married Athaliah, daughter of King Ahab of Israel. Perhaps motivated by a noble desire to reunite the tragically divided kingdom, the intermarriage actually resulted in the north having a corrosive immoral influence on the south. Daughter of Jezebel, an idolatrous, prophet-killing gentile, Queen Athaliah turned out to be as rotten as her mother, killing her own children in order to gain the throne of Judah and spread idolatrous worship. She almost subverted God’s promises that David’s line would continue, but for a grandchild who survived. The incident, which resulted from a bad marriage decision, however well-intended, is a reminder that unity and peace should never come at the cost of compromising vital principles.

Conclusion

I’ll admit that when I first read the books of Kings and Chronicles, they seemed remarkably unedifying to me. The stories of Elijah and Elisha were inspiring, but the rest of the history seemed like an endless stream of violence, broken covenants, and foolish decisions. In fact, when Nephi says his large plates contained “an account of the reign of the kings, and the wars and contentions of my people” (1 Ne. 9:4), I sometimes think that account probably read much like the books of Kings and Chronicles. It would be interesting to see what Kings and Chronicles might have looked like if they had been filtered through the work of a prophet like Mormon.

However, I’ve grown to appreciate the Biblical historical books the more time I spend with them (this awesome game helped, too!). The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are parallel books. They tell the same story—the life of Jesus Christ—with slightly different details. In much the same way, Kings and Chronicles are parallel books. They tell the same story—the history of the kingdom of Israel—with slightly different details. Perhaps, just as the gospels serve as multiple witnesses to an important story that we should all know, there is a divine reason why we’ve been given two witnesses of the history of the kingdom of Israel. That history should be especially important to Latter-day Saints because we put so much emphasis on the gathering of Israel, whose initial scattering is recorded in Kings and Chronicles. I hope this chart facilitates more people getting acquainted with these books of scripture.

This is marvelous! Thank you!

Nice infographic brother. Thanks. 🙂

Thank you to Ric for contacting me about a typo in the PDF and the blog post. I’ve corrected them (changing an errant “southern” to “northern”).

One thing I have found interesting. In total Judah had 22 Kings.

And in total Israel had 22 Kings. God gave both nations the same number of kings.

The kingdom of Judah is said to have had 8 good kings.

The kingdom of Israel is said to have had 8 assassinated kings.

The Hebrew alphabet has 22 letters.

Very interesting!

This is great! I’m reading 1 Kings and 2 Kings with my youth group. This chart will help them to see the lineage clearly. Thank you!

That’s so good to know, thanks for telling me! Are you guys reading the whole books, or selected passages? What reading program are you going by? How often are you meeting? Are you reading aloud together, or on your own and then discussing together afterward?

Thank you so much for this chart. It is very simplified and highly detailed. I was reading the Bible through and got confused when I got to 2 Kings. This chart saved me the work of going back to 1 Kings to retrace the family line. The color codes and parallel timeline arrangement of the two kingdoms is just awesome. Thank you so so much.

So good to know; thanks for taking the time to let me know! I hope you get a lot out of your reading of Kings.

Here in 2022 this is so helpful. Thank you, nice and clear.

This is a fantastic resource. Thank you!

Great graphic! Thanks.